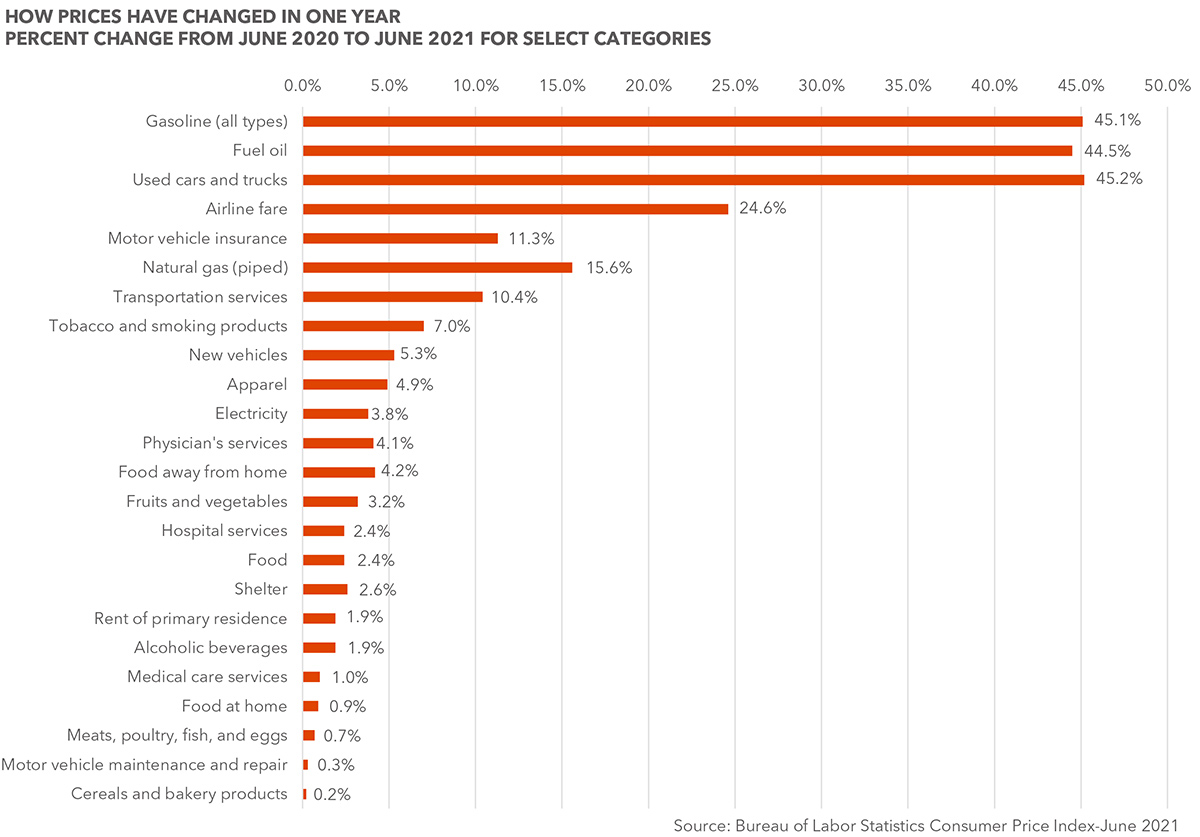

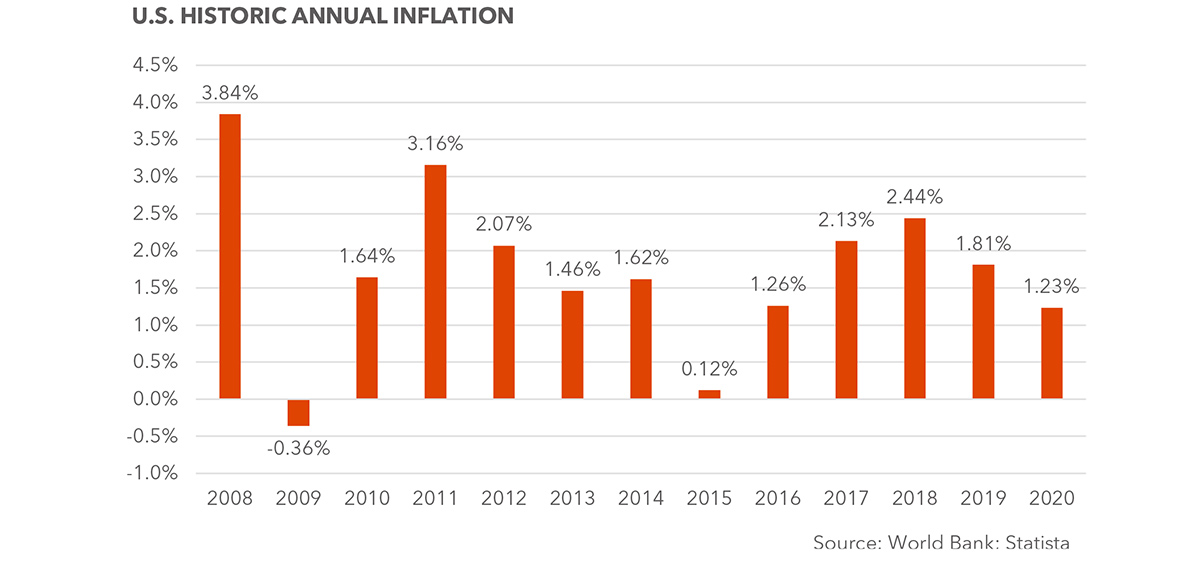

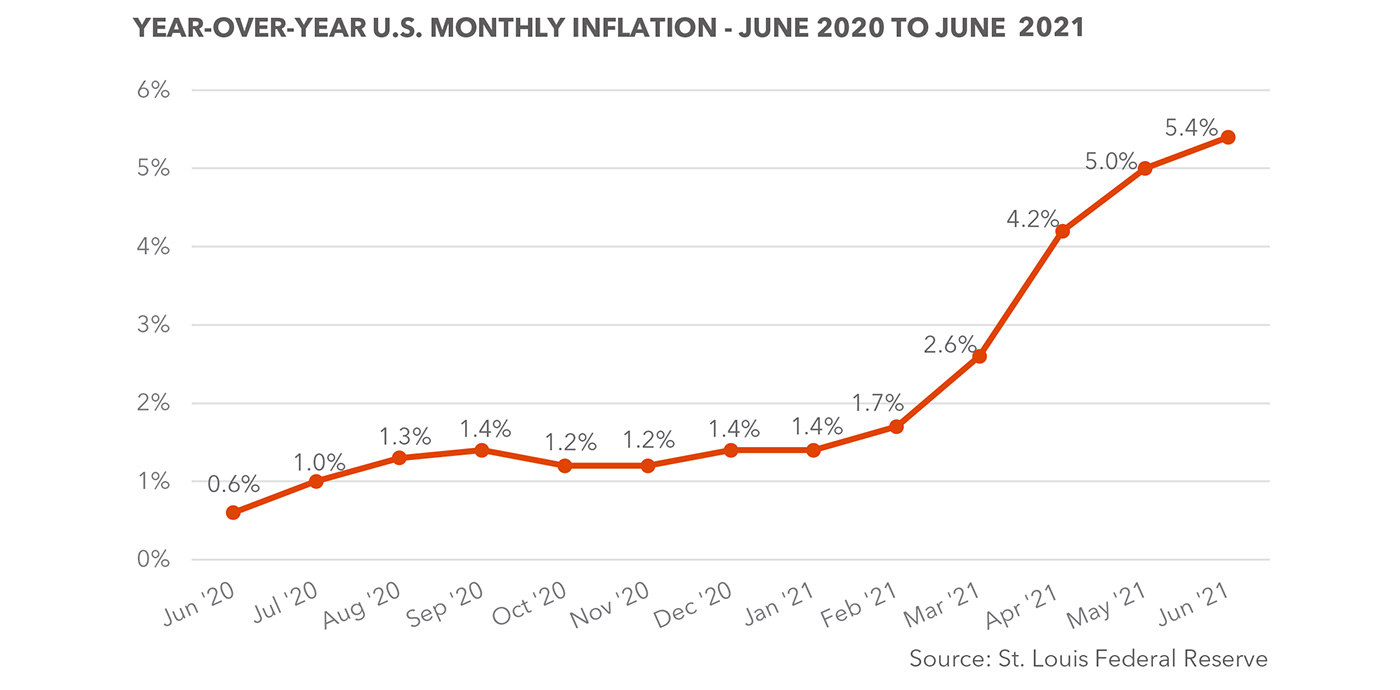

Last year’s global pandemic created the most turbulent year in living memory for the worldwide movement of goods. Global supply chain disruptions at every level—from manufacturing to transportation to logistics networks—created a severe imbalance between demand and supply that led to shortages of almost all consumer goods, electronic components, building materials, available shipping containers and truck drivers. Those shortages pushed consumer prices up 5.4% higher in June than in June, 2020, a level of increase not seen since 2008.1

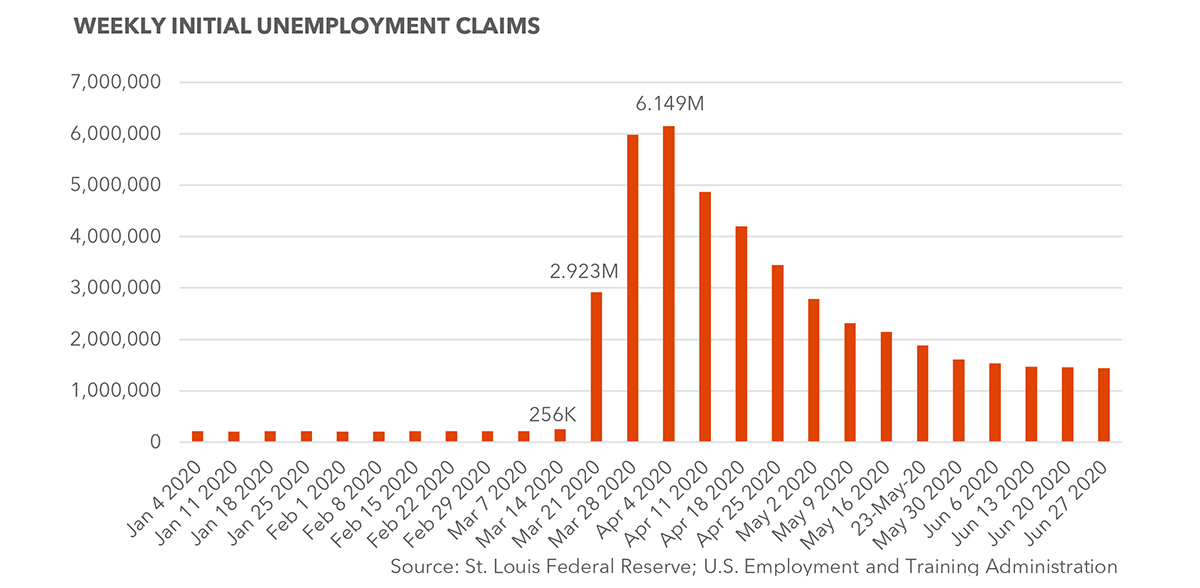

The progression of the global response to the pandemic accelerated the pace of the supply chain disruption. The early shutdown of factories in Wuhan, China in February and March of last year started the scramble of businesses around the world searching for alternative suppliers. As the virus spread, the US and governments around the world announced border closures and lockdowns in March and April that further exacerbated supply chain disruptions, business shutdowns and product shortages. The COVID recession began in the US in mid-March when mass layoffs led to 8.9 million initial unemployment claims.

Between March 21 and August 8, initial weekly unemployment claims never fell below one million.

Through the summer months production disruptions were widespread as factories were required to implement new health and safety measures with little or no notice, causing long delays in production resumption. These measures often required workspace reconfiguration to meet distancing requirements that necessarily reduced employee capacity, which in turn reduced production volume. Other factories experienced major coronavirus outbreaks before implementing safety protocols, especially in the meat processing sector. In June,11,000 COVID cases were reported from just three companies—Tyson Foods, Smithfield Foods and JBS. Remediation efforts and implementation of health and safety protocols in these companies temporarily shut down their plants, causing further production delays. Uncertainty about the course of the virus drove manufacturers to reduce inventories, reduce their workforce and cancel orders for additional inventory. In all, the pandemic caused the loss of nearly 750,000 manufacturing jobs in 2020.2

Supply chain resources that were available were diverted to supporting the “essential” businesses allowed to remain open such as grocery stores. Production was reduced or, in many cases, halted altogether across multiple product sectors not deemed “essential” in response to depressed demand. For example, US automobile sales plummeted last year when the national lockdown all but eliminated travel.3

Supply chain operation disruptions were intensified by natural disasters. A record-setting storm season in the Atlantic basin, persistent wildfires in California and Arizona that disrupted ground transportation, severe nationwide flooding in China and an unprecedented freeze in Texas all contributed to the pandemic related shortages and delays already occurring. The total blockage of the Suez Canal by the cargo ship, the Ever Given, for six days in March also heightened the global supply chain bottleneck.

By the end of 2020, the evolving disruption of the worldwide supply chain peaked with widespread product shortages, skyrocketing shipping costs and lengthy shipping delays. Even though the cost of building a new shipping container is up this year from $3,500/TEU to $3,800/TEU, the current container shortage has factories on pace to produce 20%+ more box capacity in 2021 than in the record year of 2018.4 For the week that ended July 8, the price to ship a container from Shanghai to Los Angeles was $9,631, an increase of 222% over a year earlier.5 Cargo sat unloaded in US ports like Los Angeles and Long Beach for weeks due to COVID-19 related labor shortages. Delivery of product was delayed from weeks to months once the product was actually available for shipment and delivery as the shortage of truck drivers was exacerbated by absences due to drivers contracting COVID or needing to quarantine. Those drivers available to drive were often delayed because parts needed to repair trucks were unavailable.

The perfect storm of challenges stemming from the global pandemic and a series of natural disasters is the driving force behind the inflation and delivery delays we are now experiencing. As the COVID vaccines rolled out and our economy opened, pent-up demand accelerated across the board, far outpacing the ability of the supply chain to respond. The growing demand-supply imbalance drove June’s annual inflation rate to 5.4%, its highest point since August, 2008.

Today, the future of supply chain operations is unclear at best. The recent increase in coronavirus cases attributable to the Delta variant keeps the path of the virus uncertain. While demand is now robust, manufacturers are unsure how long that will continue, keeping them hesitant to invest in increasing production capacity. What seems certain is that until the supply chain normalizes and supply catches up with demand, we can expect to pay higher prices for products that we will have to wait longer to receive.

Contact

GARY BARAGONA

Director of Research

415.229.8925

gary.baragona@kidder.com

Written by John Fioramonti

Senior Business Writer

Kidder Mathews Research

Sources

1BLS Consumer Price Index

2BLS

3Sales in 2020 fell 14.6% to 14.57 million new vehicles, the lowest number since 2012

4American Shipper Ocean newsletter, July 28, 2021

5Drewry Shipping Consultants Index